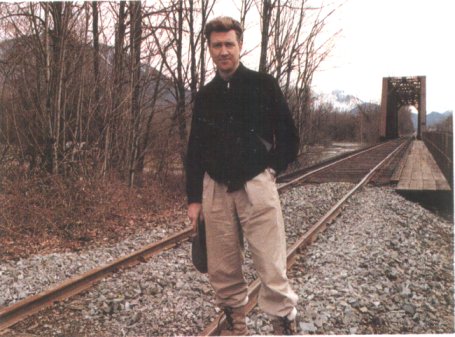

Auteur, auteur!: Two movie masters bring their

visions to the telly this month. Above, David Lynch, cocreator of Twin

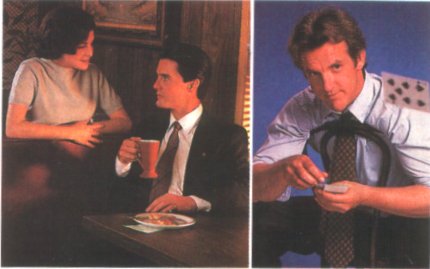

Peaks. Below, from left, Peaks freaks Sherilyn Fenn and Kyle MacLachlan,

Jamey Sheridan as the ace of John Sayles´s Shannon´s Deal.

It is the grieving that first assaults the senses. A teenage girl, Laura Palmer, has been murdered and her body, wrapped like a floral bouquet in clear plastic, has washed up on the beach near a small, isolated town in the Pacific Northwest.

The fly-fisherman who discovers the body grieves as he telephones the sheriff. The sheriff´s deputy weeps uncontrollably as he photographs the body. A few scenes later there is a horrific picture of grief: The young girl´s mother, frantic with the growing awareness that her daughter is missing, has reached the father by telephone at the lodge where he´s conducting a sales representation (a sinister sales representation, to be sure; it is the aura of evil that next assaults the senses). The father takes the call just as the sheriff walks through the doorway with the bad news. "Sheriff Truman," the father breathes into the phone; his wife, hearing this, commences wailing, her voice tinny as it keens from the now-dangling receiver that her husband, himself suffused with despair, has dropped.

There´s more. After the first commercial break, the grieving rolls ever outward in widening waves into the community. Students at the high school burst into tears as the reason for Laura´s empty seat is revealed to them. Likewise the crew-cut principal, blubbering the announcement over his oldfashioned public-address system (that´s the third assault: the dislocating perception that this strange little burg floats freely between time present and time past).

By now - some forty-five minutes into the two-hour premiere of Twin Peaks, a seven-part prime-time drama scheduled to begin on ABC this month - the grieving has begun to scrape the nerves. It may disturb or even infuriate most American TV watchers, case-hardened as they are by decades of disposable corpses that fall across the screen like hailstones, to then be adieu´d in efficient little units of rue before being whisked off-camera and utterly forgotten (except as motivating plot devices). The grieving makes one squirm: Death never hurt like this on Murder, She Wrote.

But Twin Peaks is not just another frozen Krant-burger out of the Hollywood-entertainment meat locker. Rooted though it is in the conventions of video escapism, and ambiguous in its ultimate respect for its own characters, this series will make demands seldom encountered by viewers of commercial prime time. The rewards are equally rare. Twin Peaks marks the importation to television of one of the most singular cinematic visions of the 1980s: that of writer-director David Lynch. Lynch´s Eraserhead and Blue Velvet displayed a dark, idiosyncratic avidity for the edges of American life scarcely expressed since the heyday of Orson Welles. It is time, once again, to serve that sort of wine.

In fact, the network airwaves (now there´s a time-present/time-past term: "airwaves") this late winter will see the handiwork of two important Eighties movie auteurs; the other is John Sayles, the loving custodian of American social history and anti-history (Return of the Seacaucus 7, Matewan, Eight Men Out). NBC is scheduled also his month, to introduce the full-series version of an immensely popular television movie of last June, Shannon´s Deal, which Sayle helped create and will write early episodes for. In this series, Broadway actor Jamey Sheridan, who manages to look like forty miles of bad road looking good, plays Jack Shannon, a wiped-out former corporate lawyer in Philadelphia who´s starting out all over again. His mission this time is to help the downtrodden, to fire off word-weary one-liners and to provide a foreground for Wynton Marsalis´s jazzy score.

Shannon´s Deal moved TV critics around the country to unaccustomed rhapsodies. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, scaling lyric heights previously known only to the Lake Poets, trilled that it "sneaks up with little fanfare and bites us right in the bloomers." I´m not ready to go that far. It´s wonderful stuff, but I think that Sayles - whose social themes I find admirable and compelling - has in this case produced merely a superior genre series. It is Lynch, the noir fantasist, who has more audaciously extended the boundaries of network television. It was Twin Peaks, to put it another way, that bit my bloomers. And so it is on Twin Peaks that I will herewith sit, for a while.

Three and a half years ago, Lynch crossed Edward Hopper with Dennis Hopper and shocked the living bejabbers out of mainstream American moviegoers with Blue Velvet. (He´d earlier done the same thing to the avant-garde with Eraserhead.) This ear-to-the-ground evocation of the ghastly id that festered beneath the superego of small-town American life (you sort of had to buy Lynch´s conceit that there still was such thing as small-town American life) did not satisfy all the critics - John Simon, Mr. Teflon Bloomers himself, subtly termed it "a piece of mindless junk." But others found it shocking, visionary, bruisingly sexual, full of rushing wind and the roars of animals - that sort of thing. (I saw it alone and far from home one night in St. Louis. I remember being mesmerized, both by the movie itself and by the reactions of the couples around me, most of whom seemed to be part of the spillover from the Crocodile Dundee like next 'plex. Talk about your nervous chuckling when the naked Isabella Rossellini made the peeping Kyle MacLachlan have sex with her at knife-point, or else.)

A shorthand description of Twin Peaks would be that it´s Blue Velvet filled with enough helium to last nine hours. The similarities are straightforward enough: the small-town festering-evil theme; the presence of Kyle MacLachlan as star (here the clean-cut small-town kid has grown up to be an FBI agent - small wonder after what he went through); the brooding, deep-chored score by Angelo Badalamenti, who composed for Velvet; and, perhaps above all, the eerie specificity of Lynch´s universe. Most TV dramas, even superior ones, are set in environments that are only nominally authentic; hell, they´re Televisionland. The town of Twin Peaks is as yeasty, as textured, as dreamily and semimythically its own place as you are likely to experience via the cathode-ray tube. It´s Lynch own dark Hobbitland, as unduplicable as moving water.

And yet the TV series - I have seen the two-hour pilot - stands enough apart from Blue Velvet to escape the charge of being a simple rewrite. For one thing, Lynch himself is not the sole creator. He personally directed just three of its nine hours: the pilot and one other episode (although he did block out some general guidelines for the directors of the remaining segments). And he collaborated in the writing of the series with Mark Frost, a veteran of Hill Street Blues and a partner of Lynch´s for several years.

For another, this story is framed as a murder mystery, a concession to the suspense-building requirements of serial television. No hopped-up Hopper-like character presents himself, or herself, early on as the obvious perpetrator. Part of this series´s macabre insinuation is that half of Twin Peaks (that works out to one peak, I guess) seems capable of the foul deed. Murder, Lynch wrote.

But not merely. Lynch uses the whodunit premise as a device for a methodical soulprobing of Laura´s friends, relatives and potential enemies - a kind of deconstruction of the psyche. No one is precisely as he or she might appear to be. Every single person seems to be the plot of Blue Velvet in microcosm, all picket fence on the surface, all buggy wriggle down deep. Evil is as rampant as the grieving. The deceased´s father was on the verge of doing a delegation of nice Norwegians some deep dirt on a land deal when he got the bad news. Perky waitresses are revealed as adulterous hussies. Town punks, wearing Blackboard Jungle-period drag, swagger and pirouette on hoods of cars as they chug cans of beer. A pretty high-school girl turns out to be a shoe fetishist, not to mention the kind of person who would stick a pencil into a Styrofoam cup and let all the coffee out. A bearded man in the hospital, with what seems to be large twists of paper sticking out of his ears, giggles uncontrollably at "the terrible, terrible tragedy" - and, yo, he´s the psychiatrist! In Twin Peaks there may not be a chicken in every pot but there´s a bat in every belfry.

Through this menagerie wander the two good guys (at least, I assume they´re good guys; at least they´re good-looking guys, and in Lynch´s universe I think grooming counts) - Sheriff Harry Truman, played by Michael Ontkean, and FBI agent Dale Cooper, played by MacLachlan. It is through their eyes, mostly, that we confront Twin Peaks in its many layers of psychosis. (Not that the MacLachlan character has both chopsticks in the moo goo gai pan, necessarily - he has a habit of bursting out with "Sheriff, what kinda fantastic trees you got growing around here?" at the most inappropriate times, and he´s something of a penny-pinching neatnik: "toilet-trained with a gun," to borrow novelist Hilma Wolitzer´s enduring phrase.)

It is the propensity of David Lynch´s to heap tics and warts upon even the most incidental characters that makes one wonder, eventually, exactly how he feels about the dreamlike little universes he creates so well - makes one wonder about the locus of his moral vision. For every scene of purgative grieving over Laura´s death, there is a not of freakishness: A gas-station attendant´s wife, barely glimpsed, has an eye patch; a schoolgirl´s mom, for no explained reason, is in a wheelchair. Do all these interesting little parts add up to profundity, or do they overwhelm the sum - which happens to be one good working definition of decadence?

Lynch himself is wary of the question; he´s given it some thought. "That´s a very dangerous thing you brought up," he replies in his famously ingenuous manner when I ask him about it. "People who make these things have to love these characters. It´s so easy and sick to poke fun at things. I want no part of it. Still," he adds, with understanding ambiguity, "there are absurd things that happen."

Lynch is much more forthcoming on the quality that seem to interest him the most, and which may be his most valuable contribution to television melodrama: a sense of place.

"That´s half the battle," he says. "Getting the viewer to feel the surroundings, the setting.

"Twin Peaks is a movie place, in a way; it´s not a replica of a place that could actually be. It´s the kind of place you want to go to in a daydream. It´s fun to be there. It holds the promise of many different things that could happen. And with this long form that television provides, I can do something inside a place like that that I can´t do in a feature film. I have time to discover everything about its fantastic characters. I can enter into them, get deeper and deeper, learn more and more. In Twin Peaks, the death of Laura Palmer brings out a lot of things about the town that one wouldn´t otherwise learn. I kinda like this ongoing-story thing."

Agreed. At the risk of making this sound like a convention of President Bush imitators, I kinda like David Lynch´s ongoing-story thing, too. If nothing else, Twin Peaks draws you in.

I only wish that Lynch would work on the vision thing. A sense of anxiety within his dream enclaves is fine; but America´s small towns, as battered as they are by the forces of reality, don´t deserve such a gratuitous image as Gothic loony wards. In the end, Twin Peaks would benefit from a kinder, gentler consternation.

Pulitzer Prize-winner Ron Powers writes about TV every month for GQ. A collection of his columns from the magazine, The Beast, the Eunuch, and the Glass-Eyed Child, will be published in May by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.