Hypnotic

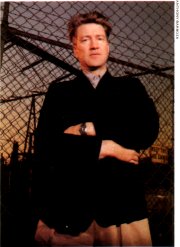

whodunit: MacLachlan and Ontkean team up to track down a murderer The body of a high

school, wrapped in plastic, washes up on the lakeshore near a small town

in the Pacific Northwest. An FBI agent teams up with local sheriff to

investigate. The victim, they discover, has been leading a secret life.

So, it seems, is nearly everyone else in town. In outline, ABC´s

heralded new series Twin Peaks sounds like an amalgam of familiar TV genres.

A touch of true-crime docudrama, a dash of Columbo, a jot of Knots Landing.

But in the darkly idiosyncratic world of director David Lynch, terms like

murder mystery and soap opera don´t begin to tell the tale. Twin

Peaks, which debuts Sunday as a two-hour movie, is like nothing you´ve

seen in prime time - or on God´s earth. It may be the most hauntingly

original work ever done for American TV. It is also something

of a miracle. Imagine: one of the world´s most perversely offbeat

directors persuades ABC to let him try a prime-time series. He shoots

a pilot with virtually no interference. The network bigwigs look at the

result, realize that it will probabyl befuddle many viewers, then decide

to air it anyway. The programmers even consider -horrors!- showing the

two-hour pilot without commercials. (Cooler heads prevail; the show will

have ads, though fewer than usual.) It´s enough to restore one´s

faith in television. The surpassing strangeness

of Twin Peaks is not easy to pinpoint. Despite a few grisly touches, the

show has little to offend in terms of sex and violence. Its distinctiveness

is almost purely a matter of style. The pace is slow and hypnotic, the

atmospher suffused with creepy foreboding, the emotions eerily heightened.

The news of Laura Palmer´s murder inspires spasms of grief in everyone

from the girl´s mother to the crew-cut school principal, who burst

into tears after announcing her death over the p.a. system. In other hands,

this might be melodramatic; in Lynch´s, it has the scalding intesity

of a nightmare. Then there

are the Lynchian touches of off-kilter characters and sideshow weirdness.

A woman with an eyepatch has an obsession with drapes. Visitors to a bank

vault find a stuffed deer head lying on the table "It fell down,"

notes a bank officer blandly. The boyish FBI agent (Kyle MacLachlan) dictates

every detail of his day into a cassette recorder and gets misty-eyed over

Douglas firs and snowshoe rabbits. "Know why I´m whittling?"

he says to the sheriff at one point. "Because that´s what you

do in a town where a yellow light still means slow down, not speed up."

Twin Peaks spins out

a whodunit that may or may not be solved by the end of the show´s

seven-week run. (For a European video version of the pilot, Lynch shot

an alternate ending that seems to solve the crime. In it, the actors walk

and speak their lines backward, and the film is reversed.) But the two-hour

movie, which spans the 24-hour period after discovery of the body, stands

superbly on its own. More than a dozen characters are introduced - all

of them connected, each dwelling in a private world - from the widowed

owner of the town sawmill (Joan Chen) to the the dead girl´s hopped-up

boyfriend (Dana Ashbrook) to the serene sheriff (Michael Ontkean), whose

name, for no particular reason, is Harry S. Truman. Whether Twin Peaks

will work as a continuing series remains to be seen. The second episode

(co-written by Lynch but directed by Duwayne Dunham) shifts into more

conventional gear as the murder investigation begins to unfold. At worst,

Twin Peaks could turn into an aesthete´s version of "Who shot

J.R."? At best, it will be mesmerizing. Few filmmakers would

seem less likely candidates for TV than Lynch. His first feature, Eraserhead,

was a dreamlike horror story about a couple taking care of a monstrous

mutant baby. Blue Velvet, his bizarre 1986 black comedy, started with

a severed ear and descended into sadomasochistic horror. Trained as a

painter, Lynch has written song lyrics and directed a performance piece,

Industrial Symphony No.1, featuring a midget sawing wood and dozens of

baby dolls lowered from the ceiling. At 44, Lynch has a

Boy Scout´s cherubic face and nice manners. His conversation is

filled with wholesome jargon like "thrilling" and "cool."

But eccentricities lurk just beneath the surface. He always keeps his

shirt collar buttoned to the top because "I have this thing about

my neck. It´s just an eerie feeling about my collarbone." For

seven years he drank milkshakes every day at a Bob´s Big Boy in

Los Angeles. "I´d have coffee, sometimes six cups, along with

the shake, and I´d have sugar in my coffee," he says. "But

then I would be pretty jazzed up, and I´d start writing down ideas.

Many, many things come out of Bob´s." Lynch, who has been

divorced and is now involved with actress Isabella Rossellini, was born

in Missoula, Mont. His father, a research scientist for the Department

of Agriculture, moved the family several time around the Pacific Northwest

before settling in Washington, D.C. Lynch found high school "worthless"

but put up with it, then went to art school in Boston. After a brieg sojourn

in Austria, he moved to Philadelphia to study at the Pennsylvania Academy

of Fine Arts. "Philadelphia,

more than any filmmaker, influenced me," says Lynch. "It´s

the sickest, most corrupt, decaying, fear-ridden city imaginable. I was

very poor and living in bad areas. I felt like I was constantly in danger.

But it was so fantastic at the same time." He lived across the street

from the city morgue, where he was fascinated by the empty body bags hung

on pegs. "The bags had a big zipper, and they´d open the zipper

and shoot water into the bags with big hoses. With the zipper open and

the bags sagging on the pegs, it looked like these big smiles. I called

them the smiling bags of death." He tried filmmaking

as an extension of his painting. Lynch´s first work was a "film

sculpture," a one-minute animated loop in which six people get sick

over and over while their heads catch fire. A painter who saw it commissioned

Lynch to make another animated film. Lynch bought a camera and spent two

months shooting before he realized the camera was broken. "It was

one long piece of blurred film," he says. "But it was the weirdest

thing; I wasn´t one bit depressed." Lynch moved to Los

Angeles in 1970 and spent five years making Eraserhead. The film became

a cult hit and led to his first mainstream film, The Elephant Man. Lynch´s

next project, the big-budgeted sci-fi movie Dune, was a critical and commercial

disaster, but Blue Velvet brought him widespread critical acclaim. A couple

of aborted projects later (including a script for Steve Martin called

One Saliva Bubble), Lynch is finishing a new film, Wild at Heart, starring

Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern. Lynch and his partner,

former Hill Street Blues writer Mark Frost, developed Twin Peaks by drawing

a map of the fictional town. "We knew where everything was, and it

helped us decide what mood each place had, and what could happen there,"

says Lynch. "The the characters just introduced themselves to us

and walked into the story." The pilot was written in only nine days

and shot in 23. Lynch was apprehensive about the restrictions of TV but

found the experience satisfying. "I didn´t feel we compromised,

and I felt good." Will TV audiences

feel just as good about the mutant soap opera he has concocted? Frost

hopes the series will reach "a coalition of people who may have been

fans of Hill Street, St. Elsewhere and Moonlighting, along with people

who enjoyed the nighttime soaps." ABC entertainment chief Robert

Iger admits the show will be a hard sell (especially in the time slot

opposite Cheers on Thursday nights.) Says he: "A lot of people have

said Twin Peaks is the critic´s dream. But is it the viewer´s

nightmare? I would hope that the answer is that it isn´t." Lynch seems confident

that viewers will catch on. "These shows could cast a spell,"

he says. "It´s sort of a nutty thing, but I feel a lot of enjoyment

watching the show. It pulls me into this other world that I don´t

know about." Well, if he doesn´t know about it, what

are we outsiders to do? Nothing but sit back and succumb to the spell. - Reported

by Denise Worrell / Los Angeles

Snowshoe rabbits, spasms of grief and dark secrets in the Northwestern

woods.

Richard Zoglin

Richard Zoglin

TIME, April 9 1990.