Take a handful of young actors and a few familiar faces, stir in a murder, add the Log Lady and what have you got? Twin Peaks, David Lynchīs surprise hit of the season. Television will never quite be the same again

Somehow, Jack Nance knew. Before heading to the Pacific Northwest to shoot a TV pilot last year, the actor had a stock answer anytime someone asked him where he was going. "I would tell them," says Nance, who would play a sawmill foreman in the show "that I was going up to make a pilot film for the big hit series of the Nineties." He laughs. "And I might have been right, you know?"

You know, he just might have been. The pilot was Twin Peaks, ABCīs twisted soap opera that would introduce network television to what actor Michael Ontkean describes as "the skewed and beatific view of the universe" held by eccentric film director David Lynch (Eraserhead, Dune, Blue Velvet). Set in a fictitous town in Washington State, the series is a wondrously warped examination of the volatile undercurrents of small-town life. "Itīs a murder mystery / soap opera with fantastic characters," says Lynch, although in all fairness, the show owes less to Knots Landingīs sudsy style than it does to Shakespeareīs juiciest works. Lynch was dead-on about the characters who inhabit the bucolic town, though. In addition to quirky folks like the Log Lady, who talks to a log she carries at all times, the two most visible characters are G-man Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) and Sheriff Harry S. Truman (Michael Ontkean), who are trying to solve the bizarre murder of popular high school coed Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee).

Twin Peaks hit the air April 8, accompanied by a barrage of reviews that agreed on two points: The show was like nothing else on television, and it was extraordinarily good. The pilot was one of the yearīs highest rated TV movies. Its first episode, airing opposite Cheers in a time slot that had destroyed many other shows, was the 13th most watched show of the week.

From the start, Twin Peaks was a bona fide phenomenon. It attracted viewers who normally watch nighttime soaps, viewers who normally watch cable, and viewers who donīt usually watch TV at all. It caused a sensation in Snoqualmie, Washington, where the pilot was shot and where the tabloids sent reporters to dig into the secrets of the small town outside of Seattle and report back that it was every bit as scandal-ridden as its fictional counterpart. The townspeople of Snoqualmie who hadnīt seen the film crew for a year - the regular episodes are filmed in a San Fernando Valley soundstage, the exteriors shot in Southern California - just laughed.

Everybody wrote about the show: Time, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, The New York Times. After the first two airings, TV Guide assigned virtually its entire reporting staff to cover it.

Pop culture devotees everywhere were watching or setting their VCRs. At a film and television convention in Canada, a Thursday-night discussion scheduled to run until 10:30 virtually emptied at 8:45 as conventioneers raced to the TV sets in their hotel rooms. In Los Angeles, one record industry publicist tried to lure people to an unnaturally early Thursday night show case performance of a new artist by making a promise: "Sheīll go on at seven oīclock sharp, because we know everbody has to be home by nine to watch Twin Peaks."

And, finally, "Within days of the pilot," says Ontkean, "people were sending script breakdowns to agents saying, 'We want this to be a little off-kilter, like Twin Peaks.'"

Jack Nance, who knows all about off-kilter - he played the title role of a zombielike freak in Lynchīs first movie, 1977īs Eraserhead - swears he wasnīt surprised. "All the talk about, 'Oh, the American publicm just wants to sit and stare at the TV,' 'Itīs over their heads,' 'They wonīt understand it,' 'Itīs great stuff, but nobody will watch it' - that hasnīt been the case at all," says the actor. "I donīt know, maybe people donīt give the public credit for having much of an attention span."

But if Nance knew this was coming, everybody else was surprised. "We never expected to come near Cheers or one of those American hamburger-type series," says veteran actor Russ Tamblyn, who plays Twin Peaks twisted psychiatrist. "For this to succedd, the whole consciousness of the American public must have been lifted a few degrees."

Thatīs one version of the story of Twin Peaks, anyway: a wild, weird show that is somehow too good not to become a hit.

But thereīs another version, and in this one David Lynch is a maverick but not necessarily a ground-breaker, his show merely a short-lived phenomenon. And at this point, as the abbreviated first season of Twin Peaks winds down (the last show airs May 24), itīs hard to tell just which version will end up being the more accurate one.

The facts, so far, are inconclusive. The pilot of Twin Peaks, riding on a wave of preshow publicity - call it genuine enthusiasm if you like the show, hype if you donīt - was an enormous success, winning its time period with a 33 share (meaning one third of all TV sets in use). "It came as a bolt from the blue, it exceeded everybodyīs expectations," says Lynch of the ratings. "I think the network thought they were hallucinating." The first episode to air in the showīs regular Thursday-night slot - when those who watched the pilot were anxious to find out who set the show in motion by torturing and killing debutante Laura Palmer - didnīt beat Cheers, but held up well. And then, the following week, viewers started going back to their old habits: Cheers regained its usually thirty-something share and Twin Peaks lost about a third of its audience.

"The show is not commercial," argues Paul Schulman, president of his own ad agency, whose clients spend approximately $175 million a year buying ads on network television. "It may be the darling of critics, it may be esthetically beautiful, it may be creatively brilliant, but it is nine leagues above the head of the normal TV viewers. All the excitement and the enthusiasm, maybe, was worth for nothing. The viewers may have loved the show, but theyīre starting to reject it."

You could call Schulmanīs attitude sour grapes, or competetive vindictiveness: Much of the money his clients spend each year goes to ads that run during Cheers. "There are an enormous number of people in this town who have a vested interest in its failure," says Paul Junger Witt of Witt / Thomas / Harris Productions, the company that produces hit shows like The Golden Girls and Empty Nest. "Lots of people in Hollywood feel threatened by something new. But Twin Peaks is the kind of thing that can keep network television important."

Still, you canīt ascribe all the doubts to jealousy or fear. (And you canīt say that the competition is unanimously negative: Cheers star Ted Danson raves that Lynch "is one of my favorite directors, so Iīm sure itīs great," and "I hope the novelty never wears off.") The morning after the second episode of Twin Peaks - which ended with what could be the most bizarre five minutes in prime-time history: a surreal dream sequence that was shot by making the actors talk backwards and then reversing the film - David Lynch made a prediction. "They may pick us up [for next season] today," he said. "Theyīre waiting to see what the numbers are. We went down last night, but itīs still better than they ever thought we would do, and weīre still doing several points above what they had in there before. I mean, I donīt know that much about how they made their decisions - but from whatīs been going on with Twin Peaks, they sorta have to pick it up."

But a few hours later, ABC entertainment president Robert Iger made it clear his network didnīt have to do anything of the sort. "Clearly, this has been phenomenal," he said, choosing his words carefully, "but I donīt think last nightīs numbers were phenomenal. Nor will you hear from me that the phenomenal nature of this will, in fact, continue. I donīt know. To date? Yes. Future? Donīt know. Thatīs really where we are."

A decision on the showīs renewal, Iger said, will be made sometime between the end of April and May 19. Meanwhile, he added, the network strongly supports the show and knows that itīs helped "immeasurably" to boost ABCīs reputation as the most adventurous of the three networks. And then, once more, he began to hedge his bets. "This experience," he said, "whether it ends up being long-term in nature, in terms of Twin Peaksī life on ABC, or whether it is in fact short-term, will still be very, very positive for us."

So the dust, for now, hasnīt settled. But what is left, and what started it all, is the most inventive, the most original, and yeah, the weirdest network TV show in years. Twin Peaks is a murder mystery that moves at a languid, dreamlike pace, a disquieting soap opera, a quietly spooky horror story. Hysterically funny and downright creepy at the same time, the mesmerizing pilot featured one corpse, two dozens continuing characters - many of whom are awesome-looking ingenues and hunks-in-training, several dozen doughnuts, and the Log Lady. And one night in April, it changed our minds about what could be a hit on American network television.

It started when Lynch, a mild-mannered, fastidious and quietly strange man who says things like "Thatīs the ticket" and "peachy keen," became interested in television after making the movies Eraserhead, Dune (1985) and Blue Velvet (1986). His screenwriter partner Mark Frost, a former story editor on Hill Street Blues, said the only way to do it would be to form their own company and own the show outright, so the money men wouldnīt be looking over their shoulders. They formed Lynch/Frost Productions and began writing a pilot, inspired first by the title Northwest Passage and then by the idea of a fictional town, Twin Peaks. They shot the pilot, which seemed like a long shot: Everybody knew that Lynchīs vision was too intense and demented for television, that Twin Peaks would be cut apart by the network censors, that even if it aired it would be ignored outside of the hipper-than-thou crowd in New York and L.A.

Even the two lead actors, ex-Rookies star Ontkean, 44, and Blue Velvetīs Kyle MacLachlan, 31, took the job figuring that it meant a chance to work with Lynch on a two-hour movie; neither of them expected ABC to actually put the damn thing on the air. But ABC liked the pilot, the censors didnīt object, and seven more episodes were ordered. "When ABC decided to go with an order of seven, I think that was the biggest shock," says MacLachlan. "And when they decided to do that, we all said, 'Well, hey, letīs have some fun.'"

Even before the show debuted, everyone in the industry was buzzing about it. Media Watchers were hounding the network for a peek at the pilot and were scheduling Twin Peaks coverage. And perhaps the people at CBSī Wiseguy series - known for inside jokes - tried to play off the show before it aired. Shortly before Twin Peaks began, Wiseguy kicked off a story line set in a Washington state village called Lynchboro, which involved lots of strange townfolk, a serial killer and featured a cop who cried when he found murdered bodies in a stream. Coincidence? Probably not.

At any rate, Twin Peaks was heralded by an unprecedented avalanche of favorable press. "Iīll tell you, that was a blitz," says William Link, the supervising executive producer of ABC Saturday Mystery and a TV veteran who was less impressed by the show - "I thought that it was a rather conventional mystery plot with some offbeat characterizations" - than by the publicity. "Usually," he says of the press, "that occurs when somebody from another field enters this medium. There are a lot of cheerleaders for that."

But ABC had just debuted another critically applauded, much-written-about show, Elvis, and that quickly disappeared. At the same time, television viewers were turning away from the three main networks in records numbers: 10 years ago 91 percent of viewers tuned to a network during the typical prime time, but last year cable and video cut that figure to 67 percent. "I was hoping for a nice little audience, like the Trekkies," admits Russ Tamblyn.

Thatīs not what happened. The pilot drew, in the words of ABCīs Iger "Nontelevision viewers, nonnetwork viewers, network viewers, older people, younger people." Robert Pittman, president and CEO of Time Warner Enterprises and the architect behind MTV, calls its debut "one of the most successful launches ever for an idea that departs from the norm."

And David Lynch didnīt know what to make of it at all. "You know, ignorance is bliss," he says of his reaction to the first batch of overnight ratings. "I didnīt know of these numbers or how fast theyīd come in. All I knew was that the pilot was on the air. And I didnīt really understand what the numbers meant when they did come in. People kept having to explain things to me: 'David, you just donīt understand how good this is.' They went out of their way to convince me that it was, you know, very good, and that something, you know, strange had happened."

And why did it happen? Lynch has an easy answer. "I think," he says, in typical fashion, "itīs just, you know, capital F-U-N."

Iger is more analytical. "I think the overall aura created about this show was eventlike in nature," explains the network chief. "This was a television event, and a lot of people get on for the ride when that happens. And also, television is no longer a new medium. And because of that, a number of concepts have been tried and reworked and tried again, and in many cases thereīs a sameness that exists. I think people were really looking forward to having a different viewing experience - and that doesnīt happen much in television these days."

Different is the key word when talking about Twin Peaks. Not only is the series populated with an abundance of off-beat characters who could never live on the cul-de-sacs inhabited by most soap land TV figures, but it chooses to deal with these people in ways that are intellectually and visually shocking. When the mother of the murdered debutante comes to realize her daughter is gone, for example, she screams, wails, and moans in unbridled agony for what seems like an eternity. In another episode, one of the characters, a wife-beater, is shown carefully putting a bar of soap into a sock and then swinging it as he closes in on his pitiful prey, his wife. Yes, Twin Peaks is decidedly different, as well as daring and disturbing.

But even after the pilot did so well, many observers figured the show would be crushed when it moved to Thursdays opposite Cheers in what is commonly known in TVas the death slot. "There was a tremendous amount of skepticism about the show regardless of where it would be scheduled, and clearly we heightened that skepticism by putting it in that period," admits Iger. "But the traditional competition was getting vanquished by Cheers year in and year out, and in this case maybe the unconventional nature of Twin Peaks was the way to compete."

Although it didnīt beat Cheers, Twin Peaks showed far more ratings muscle than anything ABC had put in that time slot in years. Over the next couple of weeks the showīs audience narrowed - it held on to younger, consumer-oriented 18-to-34 viewers, but lost many of the older viewers who were an inexplicably strong par of its early viewership - however, ratings were still high enough to suggest that viewers were more than eager for alternatives to traditional TV.

"The days of mothers trying to balance a career with a very sensitive husband sitting on the couch are over," says Married ... with Children coexecutive producer Michael G. Moye. "[The success of Twin Peaks] is Americaīs way of saying, 'Give us something different.' I think America said that very loud and clear last fall, when we came upon the most disastrous season in TV history. People want something new, and they want something different. There is nothing like Twin Peaks on TV, which is what we hear about Married ... with Children, The Simpsons, Roseanne. America is screaming loud and clear, 'We want something different - stop boring us!'"

Jack McQueen, senior vice president and general manager of the Foote, Cone & Belding/Telecom ad agency, concurs. "Maybe broadcast networks can use this to grab some of their eroding shares back," he says. "We need these kinds of things on network television to stem the tide of eroding audience to cable, VCRs, books and talking to your wife. We called last season the Season Without Reason, hopefully this next season will be Anything to Be Different Season."

Twin Peaks, he adds, "is an attempt to do something that broadcast TV can do better than anybody else, which is to deliver a weekly entertainment even that people will tune in to see because they donīt want to be the only person in the office or the neighborhood who didnīt see the last episode."

Before it can revolutionize anything, of course, Twin Peaks has to stay on the air. And if it does that, Lynch and Frost have to figure out where to go from there: how to take the promise of about $4 million pilot and fulfill it once a week, with about one-fourth the money, 22 times a year. And at the same time, they have to figure out how to hold their audience once the viewers learn the answer to the mystery that lured many people into the show to begin with: Who killed Laura Palmer?

"Itīs human nature," says Lynch, "to have a tremendous letdown once you receive the answer to a question, especially one that youīve been searching for and waiting for. Itīs a momentary thrill, but itīs followed by a kind of depression. And so I donīt know what will happen. But the murder of Laura Palmer is ..." He searches for the right way to explain that even when the audience knows the murderer, they wonīt know all the answers. "Itīs a complicated story."

By the final episode of the year, viewers will probably know the identity of the killer - but at the same time, Mark Frost says about a dozen other cliff-hangers haven been written into the final episode. (Even the cast didnīt know what would happen: When the episode was shot, they werenīt given the last few pages of the script.) "By the point that people figure out who killed Laura Palmer," says Frost, "I think weīll have created enough other interesting diversionary stories that the audience will be ready to move on to the next thing."

If next season should materialize, Frost says heīs ready: Heīs already begun working on story lines for next yearīs shows. The cast is ready: MacLachlan has a five-year contract "and Iīm going into it gladly." Lynch is ready: "I really love the show and I want to be involved. Iīll be right in there." The onetime TV neophyte can now talk about 36 shares with confidence, and he says the show can go on "way more than a year."

Thereīs only one question left, and itīs the same question that was asked before Twin Peaks ever got on the air: Is network television ready? But for all the touches that make it utterly unlike anything on the small screen, the debut of David Lynch on TV may not provoke the kind of revolution that many people that it would. Maybe, as befits the languid pace of the show itself, thereīs something quieter going on here.

"All the feedback that Iīve gotten," says coexecutive producer Mark Frost, "says that the audience is just seeing this as the next step in the evolution of the nighttime soap. Itīs still stories of people involved in mischievous behavior or trapped by circumstance or persecuted by villainy. It isnīt as if weīre not showing human behavior. In fact, I think weīre probably showing it a little more than theyīre used to seeing, and I think they respond to that."

Or, as Kyle MacLachlan says, "Hopefully, people will respond by saying, 'Oh my God, this is the strangest thing Iīve ever seen - I wanna see more.'"

Additional reporting by Mark Schwed

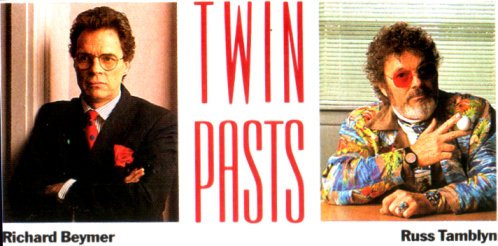

Mysteries within Mysteries. If you think all those inertwining character relationships on Twin Peaks are confusing, contemplate this behind-the-scenes twist. Actors Richard Beymer, 51 (real estate mogul Benjamin Horne), and Russ Tamblyn, 54 (psychiatris Dr. Lawrence Jacoby), have led nearly parallel lives: Both started out as child actors. Both costarred in the 1961 film West Side Story (as Tony and Riff, respectively). And while both left mainstream Hollywood shortly thereafter to pursue independent careers as progressive mixed-media artists, theyīre still best known for their roles in that classical musical about warring New York street gangs. Now that the two have achieved a measure of contemporary TV stardom with Twin Peaks, both are being dogged by questions about ... West Side Story.

And yet, like a Twin Peaks subplot, the casting of Tamblyn and Beymer is completely coincidental. They never even appear in a scene together. "I didnīt even know that they were both in West Side Story until after I cast them," says Twin Peaks creator David Lynch.

Tamblynīs audition for the role of Laura Palmerīs shrink was so high-spirited, that Lynch made him a series regular. "David had a different interpretation of [Dr. Jacoby]," Tamblyn explains. "He was supposed to be seedy and sleazy, I just decided to make him eccentric as hell."

Ironically, Beymer was originally considered for the role of Dr. Jacoby, but after meeting Lynch he was offered the role of Benjamin Horne. "I said, 'Sounds good. What does he do?' recalls Beymer. "And David said, 'He runs things.' " Itīs a role Beymerīs used to. After West Side Story, he spent two decades directing and editing his own films, including a 1964 civil rights documentary of the Mississippi voterregistration drive. Beymer returned to acting in 1983 and starred in the short-lived ABC series Paper Dolls.

Like Tamblyn, Beymer has been drawn to creating collages that he describes as "a collection of dreams, ideas, images, overheard conversations, notes and doodles." One of Tamblynīs pieces - "a collage of a big eye in a wave" - hangs on Dr. Jacobyīs office wall.

Neither actor finds it particularly odd that fate has reunited them in a pop culture vehicle. Beymer shrugs it off, saying his and Tamblynīs paths "crisscross every few years." Still, America will forever associate them with the Sharks and the Jets. "Thatīs probably something people are going to write about, isnīt it?" asks Lynch with a laugh. "Yeah, I guess itīs an interesting thing. But I didnīt even know about it."